(Sarbari Roy Chowdhury in fine Arts College, Mavelikkara, Kerala)

Close friends do not call each other just for the sake of calling. They don’t call each other because they are telepathically connected. If thick friends make long conversations just be sure that they are either transpiring aspirations or conspiring in perspiration. Soul mates make crisp telephonic chats. When they do long conversations be sure that persons at the either end or at least one of them do not have much to do at that given moment. Artists in their mid careers, as they are often anxious spend a lot of time on phone just for reassuring that other artists are not selling works the way he does these days. Artists with settled and successful careers don’t make calls because they often receive it. When they don’t receive, their secretaries do it for them.

K.S.Radhakrishnan does not call me often because we are telepathically connected. When he calls wherever I am I pick up the call because he does not call anyone for killing time. Good friends know each other’s state of mind through the tone and timbre of the voice that they hear through the phones. Yesterday, when I was in a metro coach, despite the bad signal that you get there inside the tunnels I picked up the call when I saw the screen beaming K.S.Radhakrishnan’s name. His tone was grave and I sensed something wrong. Then he said, “Sarbari da is gone.” I stood there in silence without knowing how to respond. It is difficult to respond to the news of death, especially those of close and venerable people. I immediately remembered a similar situation a couple years back. Mini Sivakumar was ailing and all of us were hoping against hope. One the news came. Radhakrishnan broke down. He clutched my shoulder and said, ‘Mini’. That was enough for me to know what had happened.

(KSR and Sarbari da in his residence in Santiniketan 2011)

Stupid you feel when you are not able to gauge the inner most pangs of a friend who has just received the news of a close friend’s demise. Sarbari Roy Chowdhury was not close to me and but he was close to Radhakrishnan and he is close to me. His pain is mine too. Like the surreal stream of blood coming out of the bullet wound from the general’s forehead, and traveling through the streets and alleys to reach the feet of his mother sitting in another town, pain travels through distance and touches the contours of my existence. If at all I could see Sarbari Roy Chowdhury, I could do that only through the eyes of Radhakrishnan. This, you may call it a shortcoming of an art historian/critic and insist that I should have known him on my own through textual analysis. But end of the day, art historical shortcomings could be a way of understanding a human being rather than his art.

First I saw Sarbari Roy Chowdhury’s sculpture in context at the Uttarayan Art Complex in Baroda. I was there to report an International Sculpture Symposium directed by Radhakrishnan. In the vast Uttarayan Complex, there is a huge sculpture of Rabindranath Tagore in his Valmiki incarnation in a play written by him. Surekha has done a video out of the installation of this sculpture there at the art complex. Standing under this sculpture and later from a distance, Radhakrishnan told me a few things about Sarbari Roy Chowdhury. For Radhakrishnan, Sarbari Da was his second Guru, though academically, he was his first Guru. But destiny and decision had it so that Radhakrishnan wanted Ramkinkar Baij to be his Guru. When Radhakrishnan prepared his dissertation and on the front page he wrote ‘To My Guru Ramkinkar Baij’, at least for a moment, he thought Sarbari Da would get hurt. But he nodded in appreciation.

(R.Sivakumar, Sarbari Da and KSR in Santiniketan)

I thought this story was a great example of human dignity. I also got a few anecdote recounted by Radhakrishnan about his second Guru. They were thick friends and remained so throughout the life of Sarbari Da. The lonely rural paths of Santiniketan had seen a very young boy riding pillion on Sarbari Da’s bicycle. They were a constant presence in the village paths. They were like a couple- Sarbari Da and Radhakrishnan- Guru and Shishya. Rural grapevine had it differently. They even thought they were having some ‘affair’ between them. Radhakrishnan and R.Sivakumar liked and revered Sarbari Da immensely. These emaciated boys unfailingly visited Sarbari Da’s home studio only to listen songs till the night crept into the next morning and to eat some delicious meals that occasionally served to them by Sarbari Da’s wife.

Sarbari Da was one of the diligent fans of Indian music. Sarbari Da hunted down Indian classical music in whichever form of recording. He started his collection when there were only LP records. Then he progressed into cassettes as the recording industry progressed along with new technologies of recording. R.Sivakumar used to quip that Sarbari Da used to look into the pockets of both acquaintances and strangers only to know whether they were having some cassettes hidden there. Such an avid collector, listener and lover of Indian music, Sarbari Da continued his passion even after he was rendered immobile by Parkinson’s disease.

(Sarbari Da blessing KSR and Mini on their marriage day)

I saw Sarbari Da closely for the first time in August 2011. We were in Santiniketan to shoot a documentary on Ramkinkar Baij as a part of the retrospective curated by K.S.Radhakrishnan. After a long day’s shoot, though the crew was tired but hopeful about a spirited night, Radhakrishnan took all of us to Sarbari Da’s home, where at the drawing room he was sitting on a sofa like cot. His eyes showed happiness through thick glasses he worn. He scanned all of us without registering much of the details. We sat around him in different chairs. The crew started clicking pictures, so did I because I did not have anything else to do than be a part of that poignant moment of a Shishya meeting his ailing Guru after a gap of few years.

I looked at the master sculptor; he was diminutive in stature. He wore an impeccable short kurta and white pyjama. I had seen a few photographs of him wearing the same kind of clothes but I had never thought that the man would be so small. Age and ailment makes men small and humility makes them huge. Perhaps, confronting each of his works in previous years might have induced a larger than life picture of him in my mind. But this man in front of me was small and I remembered meeting the legendary writer, O.V.Vijayan during his last days in Delhi. He too was small and we all thought he was too huge as we thought a writer with a huge body only could have written those influential and path breaking novels like the Legend of Khasak and the Saga of Dharmapuri. But as the moments passed by his small physique was growing before me in leaps and bounds and he occupied the whole space where we were sitting, shrinking us into molecules of men.

(KSR holding Sarbari Da's hand)

With his shivering fingers Sarbari Da touched Radhakrishnan’s hands. Then he called out ‘Radhooo’. That was the only way through which he could express his love, happiness and gratitude for a shishya who once was an integral and inseparable part of his life. He ran his fingers through Radhakrishnan’s beard, exactly the way a child does to his bearded father. I witnessed a moment of role reversal here. Radhakrishnan was overwhelmed by this gesture. We were all choking for some reason; perhaps different reasons justifiable unto the person who felt the choking then. Soon, Sarbari Da, through his gestures and finger movements told Radhakrishnan that he wanted to make a portrait of his beloved Shishya. Radhakrishnan was speechless and so were we. This is what happens when old people remember young things. This is what happens when young people confront old memories.

(Sarbari Da in one of his last public functions)

Then we walked into the night leaving Sarbari Da to his shaky memories. When an artist dies, if I borrow an expression from Arundhati Roy, he leaves a hole in the scene, not just a hole, but a hole in his/her shape. However, we try to fit in, our contours will jut out. I am talking about those artists who did their works with their hands. Factory artists must be leaving holes in the shape of clouds.

Wednesday, February 22, 2012

Friday, February 17, 2012

Discriminating the Self

(Rodney King being attacked in 1991 by the White Police)

Do artists still face social discrimination? Does the stereotypical image of an artist as an anarchist and non-conformist still rule the imagination of the larger public? The answers should be negative especially after the market boom and the self branding of artists as page 3 celebrities. If I use the liberty of spoofing the great poet, artists are the unacknowledged brand ambassadors of their own works these days. However, I should say that despite the greater visibility that the successful artists get today, a shabby looking artist or an artist with disheveled hairs and beard is often taken for a vagabond, social outcaste and at times, a terrorist.

(Bob Marley)

That means, an artist, if he or she wants to get social acceptance, should seen in branded clothes and sophisticated atmosphere. S/he should show higher level of confidence and added vigor in social mobility. It suggests that the stereotypical artist in rags has become an old story. Our paranoid society no longer wants an artist, in that case any intellectual in shabby clothes. If you have anything to do with the world, it seems to say, please wear good clothes, brand yourself and be visible everywhere. And remember, avoid the company of those people who are considered to be ‘failures’ and present yourself in the company of successful people or social climbers. Pretend that you don’t recognize your friends who have not ‘made it’ during the boom time.

I write this because I am morally agitated. I am morally agitated because still our society keeps double standards when it comes to the appearance of people. It has learnt to accept the corrupt and non-transparent if they are in good clothes, seen in expensive environment and in successful company. A talented person could be taken for a vagabond therefore a criminal only because he does not look ‘expensive’. This mentality comes from the belief in the common notion that ‘expensive’ looking people are naturally sophisticated and are incapable of committing crime. And even if they do, it is accepted as their right to be on the wrong side of the law. You may be talented but your talents should be contained in a good physique and wonderful clothes.

(Whoopi Goldberg in Color Purple)

An artist friend called me the other day and recounted an incident that he had gone through couple of days back and while telling me about it I could feel the tremors of his personal trauma. He was traveling in a train, with a reserved birth in a second class compartment. During the two days journey his right eye was infected and one side of his face looked swollen. On the third morning, as he was coming out of the washroom after nursing his smarting eyes, suddenly the ticket examiner grabbed him by the collar and tried to push him out of the running train. When he resisted and tried to walk away, the man kicked him from behind. Screaming and shouting, the ticket examiner displayed his moral responsibility for the society by saying the following words, “Scum like you spoil our society. Get out of the train.” My friend told him that he was an artist and has a valid ticket on him. But the man refused to believe it. He looked him from tip to toe. My friend is small by physique and he sports beard and long hair. Finally to wriggle out of the situation, the artist friend had to show him an identity card issued by the Lalit Kala Akademy to the award winners and show a few catalogues from his bag. The man apologized and vanished.

(Frantz Fanon)

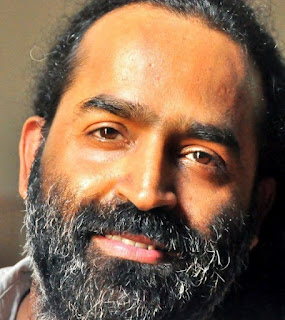

I heard my friend in pain. And I could understand his pain completely. Dark skin and beard often arouse pity and revulsion amongst the people especially in the sophisticated crowds. If you are a celebrity, then anything would go; if not, you are the scum of the earth. The wretched of the earth are still identified by dark skin. I remember a couple of incidents in which I myself was put into thanks to beard and skin complexion. When I went to Oman, security took me away even after the clearance of my papers and X-raying of luggage, and questioned me thoroughly and checked me for ‘narcotics’. And surprisingly, the heavily armed security personal who questioned me with a hostile attitude was a black man of Afro origins! Six years back I was stopped at the Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi when I was collecting my baggage. They thought the bag that I picked up from the belt did not belong to me. I was not sophisticated enough to carry that bag!

(Malcolm X)

We live in a country with a history of mendicants and wandering minstrels. We live in the land of Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi. We have been taught to adore people who have sacrificed material security and embraced the life in the wilderness and of wandering. But growing influence of globalization has made us a race that hates its own roots and complexion. We are in a dangerous world and only hope is that there is still a minority that still upholds clear thinking, resistance and humanity as their life principle.

Do artists still face social discrimination? Does the stereotypical image of an artist as an anarchist and non-conformist still rule the imagination of the larger public? The answers should be negative especially after the market boom and the self branding of artists as page 3 celebrities. If I use the liberty of spoofing the great poet, artists are the unacknowledged brand ambassadors of their own works these days. However, I should say that despite the greater visibility that the successful artists get today, a shabby looking artist or an artist with disheveled hairs and beard is often taken for a vagabond, social outcaste and at times, a terrorist.

(Bob Marley)

That means, an artist, if he or she wants to get social acceptance, should seen in branded clothes and sophisticated atmosphere. S/he should show higher level of confidence and added vigor in social mobility. It suggests that the stereotypical artist in rags has become an old story. Our paranoid society no longer wants an artist, in that case any intellectual in shabby clothes. If you have anything to do with the world, it seems to say, please wear good clothes, brand yourself and be visible everywhere. And remember, avoid the company of those people who are considered to be ‘failures’ and present yourself in the company of successful people or social climbers. Pretend that you don’t recognize your friends who have not ‘made it’ during the boom time.

I write this because I am morally agitated. I am morally agitated because still our society keeps double standards when it comes to the appearance of people. It has learnt to accept the corrupt and non-transparent if they are in good clothes, seen in expensive environment and in successful company. A talented person could be taken for a vagabond therefore a criminal only because he does not look ‘expensive’. This mentality comes from the belief in the common notion that ‘expensive’ looking people are naturally sophisticated and are incapable of committing crime. And even if they do, it is accepted as their right to be on the wrong side of the law. You may be talented but your talents should be contained in a good physique and wonderful clothes.

(Whoopi Goldberg in Color Purple)

An artist friend called me the other day and recounted an incident that he had gone through couple of days back and while telling me about it I could feel the tremors of his personal trauma. He was traveling in a train, with a reserved birth in a second class compartment. During the two days journey his right eye was infected and one side of his face looked swollen. On the third morning, as he was coming out of the washroom after nursing his smarting eyes, suddenly the ticket examiner grabbed him by the collar and tried to push him out of the running train. When he resisted and tried to walk away, the man kicked him from behind. Screaming and shouting, the ticket examiner displayed his moral responsibility for the society by saying the following words, “Scum like you spoil our society. Get out of the train.” My friend told him that he was an artist and has a valid ticket on him. But the man refused to believe it. He looked him from tip to toe. My friend is small by physique and he sports beard and long hair. Finally to wriggle out of the situation, the artist friend had to show him an identity card issued by the Lalit Kala Akademy to the award winners and show a few catalogues from his bag. The man apologized and vanished.

(Frantz Fanon)

I heard my friend in pain. And I could understand his pain completely. Dark skin and beard often arouse pity and revulsion amongst the people especially in the sophisticated crowds. If you are a celebrity, then anything would go; if not, you are the scum of the earth. The wretched of the earth are still identified by dark skin. I remember a couple of incidents in which I myself was put into thanks to beard and skin complexion. When I went to Oman, security took me away even after the clearance of my papers and X-raying of luggage, and questioned me thoroughly and checked me for ‘narcotics’. And surprisingly, the heavily armed security personal who questioned me with a hostile attitude was a black man of Afro origins! Six years back I was stopped at the Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi when I was collecting my baggage. They thought the bag that I picked up from the belt did not belong to me. I was not sophisticated enough to carry that bag!

(Malcolm X)

We live in a country with a history of mendicants and wandering minstrels. We live in the land of Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi. We have been taught to adore people who have sacrificed material security and embraced the life in the wilderness and of wandering. But growing influence of globalization has made us a race that hates its own roots and complexion. We are in a dangerous world and only hope is that there is still a minority that still upholds clear thinking, resistance and humanity as their life principle.

Friday, February 10, 2012

I Decide to Leave Mrinal- To My Children Series- 26

(Our Marriage)

On 15th August 1997, when India was celebrating its 50th anniversary of independence, I decided to end my marriage with Mrinal. Some trouble had shot up in that morning. The arguments reached a climax and I walked out of our home in Mayur Vihar Phase 3 in East Delhi. I walked, walked and walked. I saw a bus on the way and I got into it. I had not even looked at the board that said where it was going. The bus took me to the New Delhi Railway station. It was around 11 in the morning. Kerala Express was there on platform number 9. It was about to leave. I just got into the general compartment, which did not have an inch of space. The train chugged away from the station sharp at 11.20 am.

People often believe that most of the married people are happy. We see a lot of ideal couples around. But behind the facade of the ‘ideal’ I see the lurking shadows of pain, suppression, anger and violence. If you are a married person you know how difficult it is to work things out. Today, when young friends see Mrinal and myself spending time together, sharing many things and generally impart the feeling of being a ‘functional’ couple, and they believe that it is a worth emulating life, I tell them to be careful and not to be deceived by appearances. Let me tell you the truth, our marriage has never been that easy or ideal. We had tremendous personality differences and our choices were quite diversified. But when you are in love you tend to overlook all those differences. Once you are married, the differences keep coming up.

Our marriage did not work initially because we were not planning to get married. When we were in Baroda, both Mrinal and I had decided to live together but live an independent life without conventions and the bondages that came along with marriage. We thought of spending a life together like Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir (lofty ideas natural to young age). She wanted me as her life partner and that was the end of it. She did not insist on getting married but made it a point that we stayed together. In Delhi, when we rented a one room accommodation in Laxmi Nagar, we made the landlords believe that we were a married couple. They did not ask too many questions mainly because we did not look a newly married or a courting couple. We looked like two young people perfectly married for quite some time.

(Mrinal at Laxmi Nagar house)

As our friends’ circle widened and as we felt that we could alleviate ourselves from near penury, we thought of moving from Laxmi Nagar and going to a housing colony where we could afford a two room flat. While the thought was on, both my mother and Mrinal’s parents came to know about our staying together and the so called live-in relationship. It was not a surprise for them but they thought it was right time to tell us that it would be better if we got married and ‘settled’ rather than going on with the live-in relationship. We put our head together and we too felt that marriage would bring some qualitative change to our life together. We thought so mainly because the kind of rhythm and rhyme natural to the initial days of any living together relationship was slowly deteriorating. I do not want to demonize Mrinal and say that it was she who made things difficult. Nor do I want to take the whole responsibility. To cut the story short, I would say it was not working the way we thought it would and it should.

I remember, our artist friend, Roy Thomas asking one day, what Mrinal and I talked continuously even when we were in the midst of friends. Mrinal wanted to know everything. She felt insecure in the middle of a lot of Malayalis who always made it a point to talk in Malayalam without considering the presence of non-Malayali people around. I do not consider it as a problem so long as the person with different linguistic bend in the crowd does not mind it. But Mrinal wanted to know everything. She was trying to understand what we said and why we laughed and so on. She was trying her best to be a part of the crowd, which consisted mainly of bachelor boys with anarchic tendencies both in public and private domains. What I did during those occasions was translating everything as fast I could in English and Hindi so that she would feel comfortable.

Even when I was not translating things to her, we were talking something. Mostly we talked about art shows and often they ended up in fights. They ended up in fights because our views differed radically. Often we started off with some healthy arguments only to be degenerated into an ugly fight. Whatever she liked, I disliked and vice versa. Though Mrinal was very liberal, she did not like me giving too much of time to friends. She liked the same if she was around. The important factor that contributed to our growing disliking for each other was our inseparable existence. We were together all the time; we slept together, woke up together, we cooked together, we taught together, read together, drank tea together, ate lunch together, met friends together, watched movies together, went for shows together, attended programs together and even wrote articles together.

(JohnyML as an anarchist)

Writing together was the biggest of problems. As I mentioned before, our observations and opinions differed when it came to art. That does not mean that there were no points of ideological convergence at all. Whenever we agreed upon certain kind of art, we wrote things together well. The pattern was simple; I started the articles at the typewriter. Then read out it to her. She then furthered it with her observations which I converted into written form. It went on for quite some time and we came to know that it was not going to work for us. But the fear of getting separated we continued and the more we did it the more we fought. Interestingly, we did not fight for personal matters; each fight started off with art and ended up in passionate love making. In the meanwhile, language also became an issue. If I talked too much in Malayalam with my friends, Mrinal thought it was a deliberate ploy from my side to put her down. I felt the same when her brother and activist-artist, Manoj Kulkarni visited us with his painter friend, Late Kishore Umarekar came to Laxmi Nagar to spend time with us and mostly they spoke in Marathi.

Then it occurred to us that if we got married things would be different. It was the same time that our families were also compelling us to tie the knot. As we were against all kinds of social conventions and I had a special liking for being a self styled anarchist during those days, we did not want to go for a family kind of marriage. We opted for a court marriage. After seeking advice from friends and especially from Cartoonist Unny, we went to an Old Delhi court where most of the marriages were done. To our dismay we came to know that there was a ‘notice period’. They would advertise the name and pictures of the bride and bridegroom for a month or so and within that period if nobody objects the court would help them to tie the knot.

It was a lucrative and practical option for us. However, things were not that easy. We came to know that there was a parallel industry running along with the court marriages. When the names and pictures of the bride and bridegroom were published on the court notice board, a group of people came up with objections. They must be random people operating in and around the court. They may not be even the relatives of the bride and bridegroom. As these people knew that those who opted for court marriages faced some kind of objection from the families, they made it a point to take advantage of the situation. When the court told you that there was an objection, you were forced to meet these people and they settled the matter by accepting some amount of money. Some good mannered people warned us of this practice and we thought it was not good to get into trouble especially my name sounded absolutely Christian and Mrinal’s absolutely Hindu Brahmin with the surname, Kulkarni. We knew that we were in for big trouble. So we decided to avoid the route of court to get married.

(Arya Samaj Mandir, Old Rajendra Nagar, New Delhi)

Roy Thomas was a good friend and he was the first one in Delhi to start huge paintings on tarpaulin. He used to previews of his works at his rented home in Rajendra Nagar. He was a good host and entertained friends over weekends. It was through him we came in contact with another friend, Selvaraj, who was an accountant by profession but designed furniture. Soft spoken Selvan (we used to call him like that) was more comfortable with Mrinal than me. Jyothilal too was close to Mrinal because he thought I was too outspoken and arrogant. Selvan got us our first gas connection just before our marriage. We got it from Janakpuri and it was an offence to transfer gas connections without proper papers. So bringing the gas cylinder was a big problem. Selvan and me went to Janakpuri and from there we got the cylinder and connecter, got into an auto, travelled all the way to Laxmi Nagar, throughout fearing the police intervention.

In Rajendra Nagar, Roy Thomas treated us with Old Monk rum, beef, fish and whatever we thought good for a weekend. Mrinal was a strict vegetarian (and still one though she cooks non-veg with relish, discerning the taste with smelling the fragrance of the recipe) and Roy Thomas always made it a point to cook some vegetarian dishes for her. Actually Mrinal was the only girl in a predominantly male crowd of bachelors and everyone took care of her. Malayali boys are generally known for their chauvinism. However, when Mrinal was around most of them showed real concern for her and it was difficult for her to develop other friends from her own gender. She could vibe only with a very few girls like Manmeet Devgun, Kruti and Meetu Sen.

(Roy Thomas)

Roy Thomas said that there was an Arya Samaj Mandir in Old Rajendra Nagar and this temple conducted marriages without any fuss. Cartoonist Unny took us to this Mandir and the priest there agreed to get us married. We informed our relatives and my mother came to Delhi from Kerala. We were still living in Laxmi Nagar. A week before the marriage, there were ten people living in that one room including my mother and Mrinal’s parents. Though I liked friends and relatives to certain extent it was very difficult for me to spend more time in the company of people. As most of these people came to Delhi for the first time and was not aware of the ways in which this city worked, I became responsible for everything. I had to run around like a mad man to arrange things. Of course, friends were there to do things but I was the man in charge. And to add to my pains, the relatives were going full steam preparing for a formal marriage.

As idealists, Mrinal and I had decided not to depend on the money of our parents or relatives. And we refused to take any money from them. In fact we did not have much to fall back on. A joint bank account in the United Bank of India, Bengali Market that we had opened with the help of Amit Mukhopadhyaya, the then editor of Lalit Kala Contemporary Journal, was touching the danger mark. For our living, I was depending on the money from column in the Hindu Business Line, from the Hindu Group of Publications and Mrinal was making some money out of her teaching in the College of Art. I could not have jumped deadlines or abstain from writing. Preeti Mehra, the editor of the Life section in the Hindu Business Line was my anchor then. She helped me by giving chances to write more than my column and also giving chance to Mrinal to write. In the meanwhile, Mrinal had started writing for the Financial Express from the Indian Express Group.

So even when I was running around to arrange my own marriage, I had to stick to the deadlines. Writing in a room filled with twelve people including myself was a difficult thing for me. I wanted loneliness and peace. This situation made me tremendously irritable and the irritation got befitting resonances from Mrinal. Fights erupted in regular intervals. Finally we went to the Arya Samaj Mandir on 20th July 1996 and as per the Arya Samaj rituals got married in front of fire. Cartoonist Unny signed as the witness of our marriage. Roy Thomas was the master of the ceremony. N.N.Rimzon, M.J.Enas, Gigi Scaria, Cartoonist Prasad, Anil Dayanand, Sumedh Rajendran, Abhimanue V.G, Merlin, Sunitha, Santhosh Babu, Nandakumar, Bhagyanathan and so on were present during the marriage rituals. Gigi Scaria was the ‘official’ photographer of the event because he was the only one in the group at that time who had a camera. I wore a white dhoti and white shirt and Mrinal wore a red silk sari. After the rituals I changed into a pair of grey cotton trousers.

(standing L to R- Cartoonist Prasad, Roy Thomas, Sumedh Rajendran. Sitting L to R- Bhagyanathan, Anil Dayanand, Me, Mrinal, Santhosh Babu, Abhimanue VG)

We travelled back to Laxmi Nagar after marriage in a Fat Fat, the old Harley Davison jugaad vehicles that plied in Old Delhi at that time. I was carrying all the luggages, garlands and other paraphernalia of the marriage. I was feeling infuriated as I kept on thinking about condition in which I had put myself into. We were better off without marriage. Now the marriage had brought all these burdens on me. After reaching home, I had to rush out again to buy provisions for kitchen as that part was being neglected for the last few days. And on the so called ‘first night’ of our marriage, we slept amongst ten other people. There was nothing to expect or exciting about the so called first night as far as our marriage was concerned. Our marriage was consummated long back. Now what we wanted was a few moments of privacy to sort out our differences. Mrinal knew that I was angry and I knew that she was helpless. Things took an ugly turn when I refused to accompany the family members to a sightseeing trip in Delhi. Finally I had to relent and by evening when we reached the Red Fort area in Old Delhi, I jumped out of the car, hopped into a bus and went to the Barahkhamba Road in Connaught Place to deliver my article to the Hindu Business Line that I had typed out in the previous night. This action of mine brought criticism from everyone. And I just did not care and this led into a huge fight between me and Mrinal. A solution was immediately brought out by our relatives present at home. The diagnosed our problem as sex deprivation and let us sleep alone in the only room and they all went to sleep at the terrace. I don’t know whether that had really solved the problem of our marriage there.

In 1997, we could shift to a better accommodation in Mayur Vihar Phase III. It was a predominantly a south Indian ghetto but we got some wonderful neighbours who treated us with great care and love. We got a two room house with a proper kitchen, bathroom and toilet. Slowly we started buying things required for setting up a home. More than household items we gathered more and more friends. It was where our friendship with Abul Kalam Azad, the photography artist, Santhosh Babu, the hypno-therapist and Bobby Kunhu, a legal expert and activist developed in a deeper way.

(Abul Kalam Azad)

Abul Kalam Azad was a photographer with the Press Trust of India. Though he was an acclaimed photo journalist with some rare feats of covering the Hazrat Bal attack and so on, his mind was elsewhere. He wanted to become a photography artist (which he became sooner than later). He took photographs from the streets and manipulated them through certain pictorial interventions to express his religious critique. He was then living with his family in NOIDA. He got a scholarship to study in France and when he came back he was totally a changed man. He was a great cook and he threw parties whenever he found a chance to organize a party at his home with his wife’s consent. An activist with the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT), Azad had wide contacts and he travelled by a scooty.

(Santhosh Babu)

Santhosh Babu, the hypno therapist (Now one of the highly sought after corporate trainer) was another friend who came to our life and inspired us at each juncture of despair and frustration. We met Santhosh through Anil. We were told that Santhosh was working in the World Wild Life Fund at the Lodhi Road, next to the India International Centre. Santhosh was a lean thin man from Trissur and he spoke with a smile. A man of ideas, on the first meeting itself Santhosh told us that we could bring a lot of changes into our lives if we were positive towards it. Then one day we went to him home in NOIDA. He was living in the Jal Vayu Vihar Apartments. It was a very large house, befittingly shabby for a bachelor’s apartment. Anil Dayanand was a permanent fix there. Santhosh had some small birds and snakes as his pets. He surprised his visitors by taking out flowers and apple pieces from the air and from empty boxes. He was a magician too.

If any art critics had the opportunity to work as the assistants of a hypno-therapist in India, then it had come to us first. Santhosh one day told us that he was going to conduct a workshop at a school in Delhi and he needed stage assistants. Me and Mrinal went on to the stage as his assistants. Our job was to hold the people who underwent to the hypnotic sleep. He made them to do the feats that they were otherwise incapable of. He asked them to speak of their past. Some danced, some cried, some went into bouts of laughter. Later Santhosh developed and fine tuned his skills to become one of the corporate human resources trainers in India. His house in NOIDA was our week end meeting place for many years and were we used to meet friends like Praveen Thambi, the journalist, Anoop Kamath and many others.

(Bobby Kunhu)

Bobby Kunhu happened in our life during that time. While commuting back to Mayur Vihar Phase III, one day we met a person with thick spectacles in a chartered bus that started from the Barahkhamba road. He was sitting next to me and was reading some book. As I too was reading a book, he got into a conversation. He told us that he was working with the Times of India as a legal expert. In no time he said he was an aspiring writer and soon would publish an anthology of poems. He was impish and his laughter was innocent. Bobby lived in the next block in Mayur Vihar Phase III. Soon he became a regular visitor in our place and he came in touch with many artists friends who visited us over weekends. Josh PS, Gigi Scaria and Shijo Jacob were the regulars and they were all studying or finishing their studies at the Jamia Millia Islamia.

Peculiar in his life style, Bobby soon bought a second hand computer that worked only on doors format. It had a black and white monitor and he gave the impression that he was working towards his magnum opus, a novel. But what he really did was playing a game called Mine Sweeper, which was the only game available in that computer. Only one good job that computer did before going into the kabadi’s hands, was preparing Gigi Scaria’s dissertation for his MFA final. He always had ample supply of drinks at his home as he was earning well so most of us found ourselves at his home by the weekends. Bobby cooked meat and often forgot to eat. Sometimes his refrigerator was full of old food items. He always found it difficult to find his clothes so he went on buying new clothes. And when he shifted to another house, as we were helping him to pack his things, we found around thirty shirts from under his cot. Now Bobby is a social activist and spends his time in many cities including Delhi.

(Mrinal, Me, Gigi and Praveen Thampi in Mayur Vihar Phase III)

Now let me come back to my running away from marriage. I got into the crammed general compartment of the Kerala Express. I had nothing in my hand. Some army men were in the compartment and they with their muscle and uniform had occupied the seats and berths. One of them looked at me and smiled. I smiled back. In fact I was not in a mood to talk anyone. I knew that I was running away from Mrinal and as the stations passed one by one, my rage turned into fear and I was thinking only of Mrinal. What she would do? She was left alone in a city where she came totally believing in me. My fear gave way to a sense of shame. When the train crossed Mathura after two hours I thought of getting down and going back home. But my pride and ego did not allow me to do that. Once again, when the train reached Agra, the city of Taj Mahal, the monument of love, I really thought of getting down and running back to Mrinal. But my vain ego prevented me from doing that. Then stations passed in greater speed and I was going away from Mrinal.

By noon, the army man who smiled at me had eked out some information from me. I told him that I was going to Kerala as my mother was in hospital. It was a white lie. He quizzically looked at me. He asked me why I did not carry any luggage. I told him that I left home in haste and I did not even bother to pick up clothes. He did not believe it, I knew. But thankfully he did not insist. Before lunch, he offered me a glass of military rum, which I declined first and accepted later. One after another I drank several pegs of rum and got into a dreamless, fearless but shameful sleep. On the third day I got down at Kollam Railway station in an inebriated condition. My sister was working in Kollam and she was there with her friends at the platform. She saw me and was shocked. But she composed herself and took me to home. My mother did not say anything for a while. I too was quite. Once I reached home, a few phone calls had come there enquiring about me. My mother could not realize what her son had done. Once things became clear, she broke her silence with a question, “Tell me, when are you going back?” She added that she was going to book the ticket tomorrow itself. I called Mrinal and said, “I want to come back.” She did not say anything.

(Signing the marriage contract)

When I was spending three days in the train, things were going differently in Delhi. Initially Mrinal thought that I would come back by evening. It was the 50th Independence celebrations of India. As I was not seen by night, Mrinal called Anil Dayanand and he came with Azad to pick her up from Mayur Vihar III. Azad took her to a SAHMAT function where Kaifi Azmi was present. Subha Mudgal sang and Mrinal showed a brave face to everyone. Then Azad took her to his home in NOIDA and told her that they all would find a way to trace me. Next morning, Cartoonist Unny and Anil made covert attempts to see whether any dead body was found in Delhi mortuaries. Once that was not found, they assured Mrinal that I had gone to Kerala. Mrinal responded in her typical style, “Mullah ka daud Masjid Tak” (Cleric will go up to the Mosque only). What she meant was this- if at all I go I would go only back to my mother. It was Sreeni of the Hindu Business Line first made the calculations of Kerala Express’ arrival in Kerala and called my mother and casually told her that he was my friend and where I was now. My mother told him that I was living in Delhi. After a few moments I made my sheepish entry into the house with my sister.

(Better days in Mayur Vihar Phase III)

Crestfallen, ego broken and shame ridden I reached Delhi on a Saturday in the same week. By that time I had shaven off my beard and had got a normal hair cut at my mother’s insistence. I had got my eyes checked and got a pair of new spectacles. As I did not have any spare clothes and no money to buy any, my mother had bought me a pair of new clothes. So in a new attire I came back to Mayur Vihar Phase III, back to Mrinal. She received me with tears in her eyes but with befitting defiance. That evening Santhosh Babu invited us for a part at his NOIDA home, where he had invited a lot of friends. I thought they were celebrating the return of a coward. Many failed to recognize me as I was seen first time clean shaven. Anil Dayanand smiled at me with his lips curled up, a typical smile of Anil. Santhosh gave me a beautiful grin. Azad tapped at my shoulders. None asked me any questions.

(We at Taj Mahal)

After that I never thought of leaving Mrinal. I had my deviations and gallivanting after that too. We still have issues between us but I believe that we have learnt to sort them out. We have been together for the last eighteen years. But I know marriages do not happen in heaven; may be occasional juxtaposition of hell makes the glimpses of heaven more palatable.

On 15th August 1997, when India was celebrating its 50th anniversary of independence, I decided to end my marriage with Mrinal. Some trouble had shot up in that morning. The arguments reached a climax and I walked out of our home in Mayur Vihar Phase 3 in East Delhi. I walked, walked and walked. I saw a bus on the way and I got into it. I had not even looked at the board that said where it was going. The bus took me to the New Delhi Railway station. It was around 11 in the morning. Kerala Express was there on platform number 9. It was about to leave. I just got into the general compartment, which did not have an inch of space. The train chugged away from the station sharp at 11.20 am.

People often believe that most of the married people are happy. We see a lot of ideal couples around. But behind the facade of the ‘ideal’ I see the lurking shadows of pain, suppression, anger and violence. If you are a married person you know how difficult it is to work things out. Today, when young friends see Mrinal and myself spending time together, sharing many things and generally impart the feeling of being a ‘functional’ couple, and they believe that it is a worth emulating life, I tell them to be careful and not to be deceived by appearances. Let me tell you the truth, our marriage has never been that easy or ideal. We had tremendous personality differences and our choices were quite diversified. But when you are in love you tend to overlook all those differences. Once you are married, the differences keep coming up.

Our marriage did not work initially because we were not planning to get married. When we were in Baroda, both Mrinal and I had decided to live together but live an independent life without conventions and the bondages that came along with marriage. We thought of spending a life together like Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir (lofty ideas natural to young age). She wanted me as her life partner and that was the end of it. She did not insist on getting married but made it a point that we stayed together. In Delhi, when we rented a one room accommodation in Laxmi Nagar, we made the landlords believe that we were a married couple. They did not ask too many questions mainly because we did not look a newly married or a courting couple. We looked like two young people perfectly married for quite some time.

(Mrinal at Laxmi Nagar house)

As our friends’ circle widened and as we felt that we could alleviate ourselves from near penury, we thought of moving from Laxmi Nagar and going to a housing colony where we could afford a two room flat. While the thought was on, both my mother and Mrinal’s parents came to know about our staying together and the so called live-in relationship. It was not a surprise for them but they thought it was right time to tell us that it would be better if we got married and ‘settled’ rather than going on with the live-in relationship. We put our head together and we too felt that marriage would bring some qualitative change to our life together. We thought so mainly because the kind of rhythm and rhyme natural to the initial days of any living together relationship was slowly deteriorating. I do not want to demonize Mrinal and say that it was she who made things difficult. Nor do I want to take the whole responsibility. To cut the story short, I would say it was not working the way we thought it would and it should.

I remember, our artist friend, Roy Thomas asking one day, what Mrinal and I talked continuously even when we were in the midst of friends. Mrinal wanted to know everything. She felt insecure in the middle of a lot of Malayalis who always made it a point to talk in Malayalam without considering the presence of non-Malayali people around. I do not consider it as a problem so long as the person with different linguistic bend in the crowd does not mind it. But Mrinal wanted to know everything. She was trying to understand what we said and why we laughed and so on. She was trying her best to be a part of the crowd, which consisted mainly of bachelor boys with anarchic tendencies both in public and private domains. What I did during those occasions was translating everything as fast I could in English and Hindi so that she would feel comfortable.

Even when I was not translating things to her, we were talking something. Mostly we talked about art shows and often they ended up in fights. They ended up in fights because our views differed radically. Often we started off with some healthy arguments only to be degenerated into an ugly fight. Whatever she liked, I disliked and vice versa. Though Mrinal was very liberal, she did not like me giving too much of time to friends. She liked the same if she was around. The important factor that contributed to our growing disliking for each other was our inseparable existence. We were together all the time; we slept together, woke up together, we cooked together, we taught together, read together, drank tea together, ate lunch together, met friends together, watched movies together, went for shows together, attended programs together and even wrote articles together.

(JohnyML as an anarchist)

Writing together was the biggest of problems. As I mentioned before, our observations and opinions differed when it came to art. That does not mean that there were no points of ideological convergence at all. Whenever we agreed upon certain kind of art, we wrote things together well. The pattern was simple; I started the articles at the typewriter. Then read out it to her. She then furthered it with her observations which I converted into written form. It went on for quite some time and we came to know that it was not going to work for us. But the fear of getting separated we continued and the more we did it the more we fought. Interestingly, we did not fight for personal matters; each fight started off with art and ended up in passionate love making. In the meanwhile, language also became an issue. If I talked too much in Malayalam with my friends, Mrinal thought it was a deliberate ploy from my side to put her down. I felt the same when her brother and activist-artist, Manoj Kulkarni visited us with his painter friend, Late Kishore Umarekar came to Laxmi Nagar to spend time with us and mostly they spoke in Marathi.

Then it occurred to us that if we got married things would be different. It was the same time that our families were also compelling us to tie the knot. As we were against all kinds of social conventions and I had a special liking for being a self styled anarchist during those days, we did not want to go for a family kind of marriage. We opted for a court marriage. After seeking advice from friends and especially from Cartoonist Unny, we went to an Old Delhi court where most of the marriages were done. To our dismay we came to know that there was a ‘notice period’. They would advertise the name and pictures of the bride and bridegroom for a month or so and within that period if nobody objects the court would help them to tie the knot.

It was a lucrative and practical option for us. However, things were not that easy. We came to know that there was a parallel industry running along with the court marriages. When the names and pictures of the bride and bridegroom were published on the court notice board, a group of people came up with objections. They must be random people operating in and around the court. They may not be even the relatives of the bride and bridegroom. As these people knew that those who opted for court marriages faced some kind of objection from the families, they made it a point to take advantage of the situation. When the court told you that there was an objection, you were forced to meet these people and they settled the matter by accepting some amount of money. Some good mannered people warned us of this practice and we thought it was not good to get into trouble especially my name sounded absolutely Christian and Mrinal’s absolutely Hindu Brahmin with the surname, Kulkarni. We knew that we were in for big trouble. So we decided to avoid the route of court to get married.

(Arya Samaj Mandir, Old Rajendra Nagar, New Delhi)

Roy Thomas was a good friend and he was the first one in Delhi to start huge paintings on tarpaulin. He used to previews of his works at his rented home in Rajendra Nagar. He was a good host and entertained friends over weekends. It was through him we came in contact with another friend, Selvaraj, who was an accountant by profession but designed furniture. Soft spoken Selvan (we used to call him like that) was more comfortable with Mrinal than me. Jyothilal too was close to Mrinal because he thought I was too outspoken and arrogant. Selvan got us our first gas connection just before our marriage. We got it from Janakpuri and it was an offence to transfer gas connections without proper papers. So bringing the gas cylinder was a big problem. Selvan and me went to Janakpuri and from there we got the cylinder and connecter, got into an auto, travelled all the way to Laxmi Nagar, throughout fearing the police intervention.

In Rajendra Nagar, Roy Thomas treated us with Old Monk rum, beef, fish and whatever we thought good for a weekend. Mrinal was a strict vegetarian (and still one though she cooks non-veg with relish, discerning the taste with smelling the fragrance of the recipe) and Roy Thomas always made it a point to cook some vegetarian dishes for her. Actually Mrinal was the only girl in a predominantly male crowd of bachelors and everyone took care of her. Malayali boys are generally known for their chauvinism. However, when Mrinal was around most of them showed real concern for her and it was difficult for her to develop other friends from her own gender. She could vibe only with a very few girls like Manmeet Devgun, Kruti and Meetu Sen.

(Roy Thomas)

Roy Thomas said that there was an Arya Samaj Mandir in Old Rajendra Nagar and this temple conducted marriages without any fuss. Cartoonist Unny took us to this Mandir and the priest there agreed to get us married. We informed our relatives and my mother came to Delhi from Kerala. We were still living in Laxmi Nagar. A week before the marriage, there were ten people living in that one room including my mother and Mrinal’s parents. Though I liked friends and relatives to certain extent it was very difficult for me to spend more time in the company of people. As most of these people came to Delhi for the first time and was not aware of the ways in which this city worked, I became responsible for everything. I had to run around like a mad man to arrange things. Of course, friends were there to do things but I was the man in charge. And to add to my pains, the relatives were going full steam preparing for a formal marriage.

As idealists, Mrinal and I had decided not to depend on the money of our parents or relatives. And we refused to take any money from them. In fact we did not have much to fall back on. A joint bank account in the United Bank of India, Bengali Market that we had opened with the help of Amit Mukhopadhyaya, the then editor of Lalit Kala Contemporary Journal, was touching the danger mark. For our living, I was depending on the money from column in the Hindu Business Line, from the Hindu Group of Publications and Mrinal was making some money out of her teaching in the College of Art. I could not have jumped deadlines or abstain from writing. Preeti Mehra, the editor of the Life section in the Hindu Business Line was my anchor then. She helped me by giving chances to write more than my column and also giving chance to Mrinal to write. In the meanwhile, Mrinal had started writing for the Financial Express from the Indian Express Group.

So even when I was running around to arrange my own marriage, I had to stick to the deadlines. Writing in a room filled with twelve people including myself was a difficult thing for me. I wanted loneliness and peace. This situation made me tremendously irritable and the irritation got befitting resonances from Mrinal. Fights erupted in regular intervals. Finally we went to the Arya Samaj Mandir on 20th July 1996 and as per the Arya Samaj rituals got married in front of fire. Cartoonist Unny signed as the witness of our marriage. Roy Thomas was the master of the ceremony. N.N.Rimzon, M.J.Enas, Gigi Scaria, Cartoonist Prasad, Anil Dayanand, Sumedh Rajendran, Abhimanue V.G, Merlin, Sunitha, Santhosh Babu, Nandakumar, Bhagyanathan and so on were present during the marriage rituals. Gigi Scaria was the ‘official’ photographer of the event because he was the only one in the group at that time who had a camera. I wore a white dhoti and white shirt and Mrinal wore a red silk sari. After the rituals I changed into a pair of grey cotton trousers.

(standing L to R- Cartoonist Prasad, Roy Thomas, Sumedh Rajendran. Sitting L to R- Bhagyanathan, Anil Dayanand, Me, Mrinal, Santhosh Babu, Abhimanue VG)

We travelled back to Laxmi Nagar after marriage in a Fat Fat, the old Harley Davison jugaad vehicles that plied in Old Delhi at that time. I was carrying all the luggages, garlands and other paraphernalia of the marriage. I was feeling infuriated as I kept on thinking about condition in which I had put myself into. We were better off without marriage. Now the marriage had brought all these burdens on me. After reaching home, I had to rush out again to buy provisions for kitchen as that part was being neglected for the last few days. And on the so called ‘first night’ of our marriage, we slept amongst ten other people. There was nothing to expect or exciting about the so called first night as far as our marriage was concerned. Our marriage was consummated long back. Now what we wanted was a few moments of privacy to sort out our differences. Mrinal knew that I was angry and I knew that she was helpless. Things took an ugly turn when I refused to accompany the family members to a sightseeing trip in Delhi. Finally I had to relent and by evening when we reached the Red Fort area in Old Delhi, I jumped out of the car, hopped into a bus and went to the Barahkhamba Road in Connaught Place to deliver my article to the Hindu Business Line that I had typed out in the previous night. This action of mine brought criticism from everyone. And I just did not care and this led into a huge fight between me and Mrinal. A solution was immediately brought out by our relatives present at home. The diagnosed our problem as sex deprivation and let us sleep alone in the only room and they all went to sleep at the terrace. I don’t know whether that had really solved the problem of our marriage there.

In 1997, we could shift to a better accommodation in Mayur Vihar Phase III. It was a predominantly a south Indian ghetto but we got some wonderful neighbours who treated us with great care and love. We got a two room house with a proper kitchen, bathroom and toilet. Slowly we started buying things required for setting up a home. More than household items we gathered more and more friends. It was where our friendship with Abul Kalam Azad, the photography artist, Santhosh Babu, the hypno-therapist and Bobby Kunhu, a legal expert and activist developed in a deeper way.

(Abul Kalam Azad)

Abul Kalam Azad was a photographer with the Press Trust of India. Though he was an acclaimed photo journalist with some rare feats of covering the Hazrat Bal attack and so on, his mind was elsewhere. He wanted to become a photography artist (which he became sooner than later). He took photographs from the streets and manipulated them through certain pictorial interventions to express his religious critique. He was then living with his family in NOIDA. He got a scholarship to study in France and when he came back he was totally a changed man. He was a great cook and he threw parties whenever he found a chance to organize a party at his home with his wife’s consent. An activist with the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT), Azad had wide contacts and he travelled by a scooty.

(Santhosh Babu)

Santhosh Babu, the hypno therapist (Now one of the highly sought after corporate trainer) was another friend who came to our life and inspired us at each juncture of despair and frustration. We met Santhosh through Anil. We were told that Santhosh was working in the World Wild Life Fund at the Lodhi Road, next to the India International Centre. Santhosh was a lean thin man from Trissur and he spoke with a smile. A man of ideas, on the first meeting itself Santhosh told us that we could bring a lot of changes into our lives if we were positive towards it. Then one day we went to him home in NOIDA. He was living in the Jal Vayu Vihar Apartments. It was a very large house, befittingly shabby for a bachelor’s apartment. Anil Dayanand was a permanent fix there. Santhosh had some small birds and snakes as his pets. He surprised his visitors by taking out flowers and apple pieces from the air and from empty boxes. He was a magician too.

If any art critics had the opportunity to work as the assistants of a hypno-therapist in India, then it had come to us first. Santhosh one day told us that he was going to conduct a workshop at a school in Delhi and he needed stage assistants. Me and Mrinal went on to the stage as his assistants. Our job was to hold the people who underwent to the hypnotic sleep. He made them to do the feats that they were otherwise incapable of. He asked them to speak of their past. Some danced, some cried, some went into bouts of laughter. Later Santhosh developed and fine tuned his skills to become one of the corporate human resources trainers in India. His house in NOIDA was our week end meeting place for many years and were we used to meet friends like Praveen Thambi, the journalist, Anoop Kamath and many others.

(Bobby Kunhu)

Bobby Kunhu happened in our life during that time. While commuting back to Mayur Vihar Phase III, one day we met a person with thick spectacles in a chartered bus that started from the Barahkhamba road. He was sitting next to me and was reading some book. As I too was reading a book, he got into a conversation. He told us that he was working with the Times of India as a legal expert. In no time he said he was an aspiring writer and soon would publish an anthology of poems. He was impish and his laughter was innocent. Bobby lived in the next block in Mayur Vihar Phase III. Soon he became a regular visitor in our place and he came in touch with many artists friends who visited us over weekends. Josh PS, Gigi Scaria and Shijo Jacob were the regulars and they were all studying or finishing their studies at the Jamia Millia Islamia.

Peculiar in his life style, Bobby soon bought a second hand computer that worked only on doors format. It had a black and white monitor and he gave the impression that he was working towards his magnum opus, a novel. But what he really did was playing a game called Mine Sweeper, which was the only game available in that computer. Only one good job that computer did before going into the kabadi’s hands, was preparing Gigi Scaria’s dissertation for his MFA final. He always had ample supply of drinks at his home as he was earning well so most of us found ourselves at his home by the weekends. Bobby cooked meat and often forgot to eat. Sometimes his refrigerator was full of old food items. He always found it difficult to find his clothes so he went on buying new clothes. And when he shifted to another house, as we were helping him to pack his things, we found around thirty shirts from under his cot. Now Bobby is a social activist and spends his time in many cities including Delhi.

(Mrinal, Me, Gigi and Praveen Thampi in Mayur Vihar Phase III)

Now let me come back to my running away from marriage. I got into the crammed general compartment of the Kerala Express. I had nothing in my hand. Some army men were in the compartment and they with their muscle and uniform had occupied the seats and berths. One of them looked at me and smiled. I smiled back. In fact I was not in a mood to talk anyone. I knew that I was running away from Mrinal and as the stations passed one by one, my rage turned into fear and I was thinking only of Mrinal. What she would do? She was left alone in a city where she came totally believing in me. My fear gave way to a sense of shame. When the train crossed Mathura after two hours I thought of getting down and going back home. But my pride and ego did not allow me to do that. Once again, when the train reached Agra, the city of Taj Mahal, the monument of love, I really thought of getting down and running back to Mrinal. But my vain ego prevented me from doing that. Then stations passed in greater speed and I was going away from Mrinal.

By noon, the army man who smiled at me had eked out some information from me. I told him that I was going to Kerala as my mother was in hospital. It was a white lie. He quizzically looked at me. He asked me why I did not carry any luggage. I told him that I left home in haste and I did not even bother to pick up clothes. He did not believe it, I knew. But thankfully he did not insist. Before lunch, he offered me a glass of military rum, which I declined first and accepted later. One after another I drank several pegs of rum and got into a dreamless, fearless but shameful sleep. On the third day I got down at Kollam Railway station in an inebriated condition. My sister was working in Kollam and she was there with her friends at the platform. She saw me and was shocked. But she composed herself and took me to home. My mother did not say anything for a while. I too was quite. Once I reached home, a few phone calls had come there enquiring about me. My mother could not realize what her son had done. Once things became clear, she broke her silence with a question, “Tell me, when are you going back?” She added that she was going to book the ticket tomorrow itself. I called Mrinal and said, “I want to come back.” She did not say anything.

(Signing the marriage contract)

When I was spending three days in the train, things were going differently in Delhi. Initially Mrinal thought that I would come back by evening. It was the 50th Independence celebrations of India. As I was not seen by night, Mrinal called Anil Dayanand and he came with Azad to pick her up from Mayur Vihar III. Azad took her to a SAHMAT function where Kaifi Azmi was present. Subha Mudgal sang and Mrinal showed a brave face to everyone. Then Azad took her to his home in NOIDA and told her that they all would find a way to trace me. Next morning, Cartoonist Unny and Anil made covert attempts to see whether any dead body was found in Delhi mortuaries. Once that was not found, they assured Mrinal that I had gone to Kerala. Mrinal responded in her typical style, “Mullah ka daud Masjid Tak” (Cleric will go up to the Mosque only). What she meant was this- if at all I go I would go only back to my mother. It was Sreeni of the Hindu Business Line first made the calculations of Kerala Express’ arrival in Kerala and called my mother and casually told her that he was my friend and where I was now. My mother told him that I was living in Delhi. After a few moments I made my sheepish entry into the house with my sister.

(Better days in Mayur Vihar Phase III)

Crestfallen, ego broken and shame ridden I reached Delhi on a Saturday in the same week. By that time I had shaven off my beard and had got a normal hair cut at my mother’s insistence. I had got my eyes checked and got a pair of new spectacles. As I did not have any spare clothes and no money to buy any, my mother had bought me a pair of new clothes. So in a new attire I came back to Mayur Vihar Phase III, back to Mrinal. She received me with tears in her eyes but with befitting defiance. That evening Santhosh Babu invited us for a part at his NOIDA home, where he had invited a lot of friends. I thought they were celebrating the return of a coward. Many failed to recognize me as I was seen first time clean shaven. Anil Dayanand smiled at me with his lips curled up, a typical smile of Anil. Santhosh gave me a beautiful grin. Azad tapped at my shoulders. None asked me any questions.

(We at Taj Mahal)

After that I never thought of leaving Mrinal. I had my deviations and gallivanting after that too. We still have issues between us but I believe that we have learnt to sort them out. We have been together for the last eighteen years. But I know marriages do not happen in heaven; may be occasional juxtaposition of hell makes the glimpses of heaven more palatable.

Saturday, February 4, 2012

Finding Friends in Delhi- To My Children Series 25

(Anil Dayanand- picture by Leo James)

When you have nothing, you feel that you have a lot to give to others. When you have something you feel that you can keep something and share a part of it with others. When you have too many things, it is often observed that you don’t feel like giving anything to anybody. It is not a rule, exceptions are aplenty. In that case, it is always better to have something so that you can share a part of it with others because you are not too full and that makes you feel that others too need things. When you are too full your visions get blurred. Am I talking about the spiritual side of life or the materialistic side of it? I think I am talking about the materialistic side. That’s the way I feel. That’s how my life in Delhi became possible. And today I can say that I have something, a little bit of things so that I can share with others. But there was a time when I did not have anything. And I thought that I could give the whole to others. That was a dream. Caught between dream and reality, I found friends who had something to share with me; their lives, their passions, their dreams, their money. That was how my life started spreading its roots in the soil of Delhi.

Anil Dayanand was one friend who came first in our life. There were many but Anil stood apart because he was always ready to give anything and everything that he had to anyone who wanted it. He had abundance of love. Anil Dayanand, when I write this is still around and I bump into him once in a while when there are exhibition openings and other social functions in which both of us get invited accidently or we get ourselves self- invited. Anil was then the editorial illustrator of the ‘Business and Political Observer’ Newspaper published from Delhi. We met him at the Lalit Kala Akademy lawns and it was love at first sight. Anil became friendly very quickly followed by cups of tea and cigarettes at the Lalit Kala Akademy canteen. What I noticed in Anil was his ability to talk about art without any hesitation. He had opinion about all what had been going on in the art scene. He could speak English well with an accent which was not affected. And whoever walked into the Lalit Kala Akademy premises knew Anil and whoever knew Anil slowly became our friends too.

After taking BFA in sculpture from the Trivandrum Fine Arts College, Anil came to Delhi to pursue his post graduate studies and he took masters in sculpture from the Delhi College of Art. As a person who could fit into any situation with his conceptual talks, Anil used to hang out at the Delhi College of Art canteen even years after he finished his post graduation. Following the true tradition of the Trivandrum Fine Arts College, where the teachers conduct the day courses and the former pass outs take the evening classes to the students at the canteen, cycle shed and courtyard, Anil took classes for the under graduates in the Delhi College of Art in the canteen and elsewhere and initiated most of them into conceptual thinking. Anil’s day started at his home or any friend’s home where he was drinking and smoking at the previous night and with the first ray of the sun, he reached the college in his blue denims and tucked in striped cotton shirt. By afternoon he reached the Lalit Kala Akademy library and read till evening. After that he left for his office at the Barakhmba Road near Connaught Place and spent a few hours there making graphic illustrations for the editorial page articles. Soon we too became a part of this routine.

(Anil Dayanand)

Anil used to be known amongst friends as ‘thumbs up’ as he had an extra finger at his right palm. Even when he kept his fist clenched, this finger jutted out addressing the world as if it were an organ with a separate life from that of Anil. Years later, when Anil came back from Botswana, where he had gone on a teaching job, he had loads of charcoal drawings of nude black women whom he had befriended there. But something was missing in him and that was his extra finger. When asked he with his innocent smile responded to us saying that he had got it operated because the finger was inviting a lot of attention. Famous film star Hritik Roshan too has an extra finger at his right palm and it is considered to be lucky for him. We used to joke that Anil’s luck resided in his extra finger. But even after he lost it, Anil remained the same without much luck in the art scene. I would say that Anil is perennially lazy and derives happiness in ideating than executing those ideas into material forms. He gets frustrated when he sees his ideas getting reflected in the works of other artists. I do not say that other artists plagiarize Anil’s ideas but as we are all living in the same time and same urban locales, it is natural to arrive at same kind of ideas. Anil dips his frustration into alcohol and burns his woes in thick curls of smoke.

Before I get on with the story of Anil and his friends who are to become our friends too sooner than later let me tell you the story of our settling down in Delhi. You must be remembering me telling about N.N.Rimzon’s offer to me when I visited him in an art camp sometime in 1994. He had told me to contact him if I happened to be in Delhi. That was the one hope we had when we set out our journey to Delhi. We asked Anil to take us to Rimzon’s place. During those days Rimzon was living in Laxmi Nagar towards the Patpatganj side. Today also struggling artists live in Laxmi Nagar and I had written about it in one of my blogs published a few years back. Noted artists like Subodh Gupta, Bharti Kher, Manjunath Kamath and so on all had started their Delhi life in this part of the city. Anil told us how to get there and on the third day of our arrival we went to see Rimzon at his place. I don’t know whether he was expecting us or not. Whatever be the case when he saw us at his doorstep he warmly welcomed us and treated us well. He was patiently listened to our plans and also with a shock he imbibed the fact that we did not have any money. After thinking for a few seconds he said that he could lend us some money so that we could start our life in Delhi. He offered us a princely sum of Rs.3000/- We were really happy.

(N.N.Rimzon at his Laxmi Nagar studio sometime in mid 1990s -pic by Abul Kalam Azad)

I should say we were extremely lucky and we did not have anything in our hand except for two bags. But our treasures were increasing and we were getting richer by day through friends and their warmth and love. Anil had taken us to the Delhi College of Art as his prized possessions from Baroda; me, a specimen of anarchic looks and Mrinal, a young thin girl with undefined future with a person like me. There at the college we met Abhimanue V.G, a painter who had also studied in Baroda and then a lecturer at the painting department in the Delhi College. Abhimanue looked like an artist from tip to toe. He had closely cropped hairs and a goatee. He talked with an accent thanks to his peculiar jaw bones. He dressed stylishly and then rode a motor bike.

In his studio cum office room Abhimanue had many canvases and drawings. He painted romantic landscapes as they were derived from the Indian miniatures and there were always women and men looking at each other longingly. Soon I realized that he was a perennial romantic. He greeted us with a smile that soon verged into a guttural laughter. He ordered tea for us and offered me his packet of Gold Flake cigarettes. After enquiring about our days in Baroad and also after talking extensively about his friends and acquaintances and their stories in Baroda, he took us to the head of the department, Mr.Vijayamohanan. He also welcomed us in a friendly manner. He ordered for tea and tea came in porcelain jugs and cups. He made tea for us and asked us what we were planning for our future. Future looked grim and the brightness was seen only in our eyes. I looked at Mrinal and she looked at me. And then we both looked at Abhimanue and Vijayamohan. Then Vijayamohan asked a question that made us feel good and happy.

(Abhimanue VG)

“Would you like to join as guest lecturers here?” Vijayamohan asked us.

We could not have said anything that faintly sounded negative. So we immediately said that it would be a pleasure and honor if we got chance to teach in the college. He asked us to fill in the application forms then and there and promptly we did so with the help of Abhimanue. And the next day we were appointed as guest lecturers. I was given the foundation course and it was my duty to initiate the new students to art history. Most of the students liked my anarchic looks and they did not realize the fact that the anarchic look came mostly from deprivation. I used to ask myself had I been at home with my mother would I have walked around like that in baggy clothes, disheveled hairs and overgrown beard. My mother would not have approved of my looks. Even if she had the neighbors and the local people would not have allowed me to walk like that because whenever I visited Kerala in that attire people used to ask me whether I was okay and some of them were even audacious to ask my mother whether I was having some mental problem.

I was happy to teach the fresh students because I too was fresh in teaching as far as art history was concerned. I did not have any stage fright when I was on the platform because I had the habit of teaching from a very early age itself. But art history was something different. Mrinal was good at teaching and she made her career in teaching and she is an Assistant Professor at the Art History department in the Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. My story with teaching was a short lived one; it lasted only one year. In any institution inside politics is rampant and Delhi College of Art was no exception. Somehow, some people in the college started feeling insecure as the students were gravitating towards us. And as we were in the College, whoever came from Baroda used to drop into say a hello. Art scene was not ridden by glitter and glamour during those days and the art people were much more humane. They took all the pain to come and meet us in the college. Soon this gave the impression that I was trying to create a Baroda lobby in the College. The institutional egos worked against me in a way and I was not invited to teach in the College again. That was the end of my teaching career. Years later when the institutions in this country invite me to give lectures and take semester classes, I accept the offers with a smile and I remember the days of my eviction from the Delhi College of Art.

(Delhi College of Art New Building)

We had roti (food), kapda (clothes) but makan (home) was not there for us. The life in the Lalit Kala Akademy guest house was not quite appealing after a week and it was urgent to find a place to live. Friends told us that ‘rooms’ were available in some of places and we did not like this idea of ‘room’. We wanted a home where we could live and work. Now with Rs.3000/- in hand given by Rimzon we thought of looking for a house where we could set up our home. It was then Anil came forward and introduced us to Jyothilal T.G and Sabu Joseph, two sculpture students there in the Delhi College of Art. They said they lived in the trans-Yamuna area near Laxmi Nagar and it would be a great idea to look for an accommodation in Laxmi Nagar. We too liked it as we thought we would have known friends like Rimzon and these students there and we would not be lost in a new place. So one evening Jyotilal took us to Laxmi Nagar to hunt for a house in Laxmi Nagar.